Writings

Foreword to Ornette Coleman’s Biography

1999

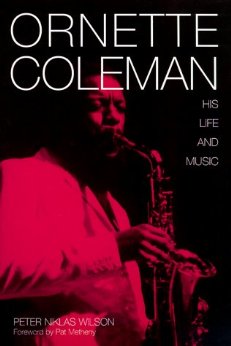

Pat Metheny’s foreword to the book: Ornette Coleman: His Life and Music by P.N. Wilson – June 1999

********************************************

Ornette is all about inspiration in music.

Ornette is all about inspiration in music.

With Ornette, there is always so much more to talk about than the actual notes. The vast implications of what he has offered the world as an improvisor, bandleader and composer will be studied and scrutinized by every new generation of players for generations to come. And there will always be plenty of musical features to talk about in those discussions; his amazing sound, his way of phrasing,of developing each idea to it’s natural conclusion his harmonic concept, and so much more are quantifiable to the degree that we can even discuss them. But for this listener, Ornette’s thing transcends what he actually plays – it is something that goes far beyond just that.

Ornette is the rare example of a musician who has created his own world, his own reality, his own language – effective to the point where emulation and absorbtion of it is not only impossible, it is simply too daunting a task for most musicians to even consider. In the world of acoustic jazz, where Ornette left off just prior to forming his electric band prime-time in the 70’s is so far ahead of where even the best players of today jazz scene are that it borders on the inexplicable. And his long running efforts to deal with the challenge of electricity have produced some of the very few efforts in that area to transcend the wires and knobs and buttons to ascend to true soul music.

My own personal contact with Ornette Coleman’s music, and later the man himself, remain among the most important and influential parts of my life as a musician. As a young player growing up in missouri trying to learn about music, it was natural that I would aspire to learn as much as I could about a major musician such as Ornette and his music by listening to his records and trying to understand everything I could about this way of playing that seemed to include many of the same mechanisms as the bebop and post-bop language that I was also working hard on, but somehow transcended it at the same time. It seemed to me, in my naive state of having been a listener for just over a year, that these were musicians who in addition to being incredbly advanced and sophisticated, were also having an especially great time making the music that they were making – something had more than a little impact on my then 14 year old conciousness. As I got deeper and deeper into their music, I naturally tried to quantify just exactly why I loved it so much. I realized that this music (specifically the records “Change of the Century”, “This is Our Music”, and “New York is Now”) had many of the same qualities that ALL of my favorite music had – from Bach to the best country music of the time to the Beatles to Miles Davis – there was an inevitableness to the lines and the spirit behind them, they HAD go the way they went – no note could be any note other than the note it was. But somehow these guys were doing it on the spot, as a band.

The way that Ornette and bassist Charlie Haden could listen to each other and make these incredible webs of implied harmony that evoked everything from the blues to the most advanced counterpoint of western classical music was one of the most deeply musical things I have experienced as a listener. The orchestrational aspect of the piano-less quartet, especially on the early records showed a sensibility and economy of purpose that allowed an expansiveness to emerge through the reduced instrumentation of the traditional jazz lineup that was revolutionary and remains modern to this day.

Ornette’s contributions, musically, philosophically and spiritually, have inspired almost 40 years worth of young musicians to look inside themselves to find things that they simply might never have found had he not so successfully created his own personal language of music, illuminated by the brightest possible light of what one person with a strong vision of sound and music can accomplish.

In the early 1980’s I had been playing in a trio regularly with Charlie Haden and drummer Billy Higgins and Ornette had come down to the village vanguard during one of our New York engagements to hear us play. I think that Ornette knew that I had recorded a few of his songs here and there over the years and seemed to have a special growing interest in the guitar as a potential sonic element in the music. Over the course of a few conversations, (with constant encouragement on both sides by our mutual friend Charlie) we agreed that it would be fun to get together sometime and play.

Shortly after that, I changed from one record company to another, and these conversations stuck in my mind. With one call to Ornette, one to denarndo (his son and manager,) we agreed that we should make what would become the record Song X; it would be my first record for this new record company (Geffen) and a major highpoint in my life as a musician.

The weeks leading up to the making of this record were really intense, and unbelievably inspiring. In our first meeting, we agreed that we should try to do something that was unlike anything that might be expected of either of us – and that we should try to develop a language and a way of playing together that was particular to this project. We began a routine that would last almost a month – of getting together just the two of us, sometimes with denardo joining in on drums, and play together for as much as 10 hours a day, working on tunes and ideas for the record; and spending countless hours just playing together. after a few weeks of this, we started to come to some conclusions about what other musicians would be ideal to join us.

The rhythm section of myself, Charlie and Jack DeJohnette had done a fair amount of playing together by that time (we had made a record called 80/81 a few years before that and had toured alot, and then again as a trio). I felt that the meeting of Jack and Ornette would be exciting, and the work that Denardo was doing with electronics was fascinating to me and seemed to parallel some of what I was working on with my own guitar synth at that time. I have to admit too, that I was most excited to hear Charlie and Ornette play together again – at the time of this record it had been almost 10 years since they had recorded together.

It was an amazing opportunity to really examine Ornettes thinking processes as well as learning a lot about improvising itself from one of the genuine living masters. But during this process, and (even more so) on the tour that followed, I was struck by just how much sheer time and energy Ornette puts into his music. I have been accused of being a “workaholic” myself – known to spend countless hours practicing, working on a new project or tune or record – but in Ornette I had more than met my match. I recall on the tour (all one-nighters across the U.S., a fairly grueling schedule) that we would check into a hotel at noon or so, Ornette would immediately go to his room and start practicing, playing right up to the soundcheck at four pm. He would then play all through the soundcheck (I remember at one point asking him to stop for just a few minutes so I could work on a technical thing with a volume pedal or something without having to shout over the music to the sound crew!). He would then stay at the gig, and practice right up till the first note of the concert, play so beautifully (and long!) for the gig (we were averaging 2 to 2 and 1/2 hour sets), and then stay afterwards and play some more after the gig. I have never seen any musician of any age with that kind of dedication and just plain stamina. Also, it was interesting to hear just exactly WHAT he was practicing. First of all, it didn’t sound like “practicing” at all, it was more like playing itself – with an occasional pause to mine a newly discovered tributary of an idea, which when you think about it is kind of a characteristic of his on the bandstand playing as well. Also, I remember being struck by just how tuneful and songful his “practicing” was – I remember thinking that there were dozens of great Ornette tunes being generated by the second, and that there seemed an almost infinite supply of them in there.

In addition to being one of the giants of modern music, Ornette is one of the most gentle and soulful human beings on the face of the earth. His humor, so evident in his music, informs all aspects of his off-the-bandstand behavior as well – his music being literally a perfect reflection of the man inside. And his in humility, in the face of his overwhelming accomplishments and abilities, we find a reserve of personal wisdom that matches his gift as a musician.

However, for all the things that I have personally gotten out of listening to, playing and being around Ornette’s music, I have to say the main thing in the end that has affected me the most – and inspired me the most – is Ornette’s profound commitment to developing his own personal musical language. The way he has relentlessly assumed responsibility for his own singular musical aesthetic may be one of the most important beacons of artistic vision and clarity of our time. He has inspired me, and by this time it must be thousands of other musicians, to answer to a standard that demands that we look into our OWN hearts and minds to see what we may have to offer in OUR own personal musical languages – if we can only muster up the courage to listen to the songs inside of us the way Ornette has. This quality, becoming more and more rare, less and less valued in this era of conservatism and revisionism that these words are being written in, is the lasting gift that Ornette has given the music world that will provide future generations of musicians from all stylistic areas a point of reference forever. Here was a man who made his own music, his own way – with nearly unparalleled artistic success.